Grain storage is a key component in the agribusiness landscape, playing a fundamental role in logistics and the competitiveness of the sector. When we look at the Brazilian scenario, we observe a recurring problem in our country: the shortage of warehouses.

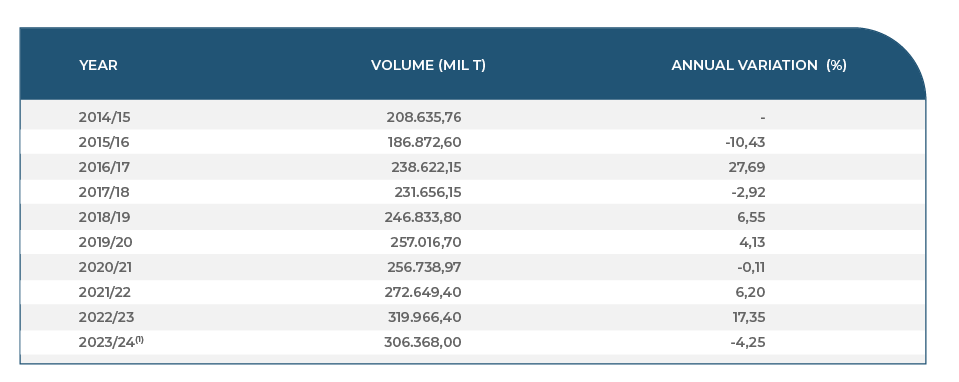

Speaking of expectations, the forecasted production for the 2023/2024 grain harvest is 306.37 million tons (Conab), a 4.25% decrease from the 2022/2023 harvest, in which Brazilian production reached a record (319.83 million tons). Refer to Table 1.

Although it has decreased, the storage deficit remains significant.

Table 1

Volume and annual variation of Brazilian grain production.

¹ Projection by Conab (January 2024). Source: Conab / Prepared by Scot Consultoria.

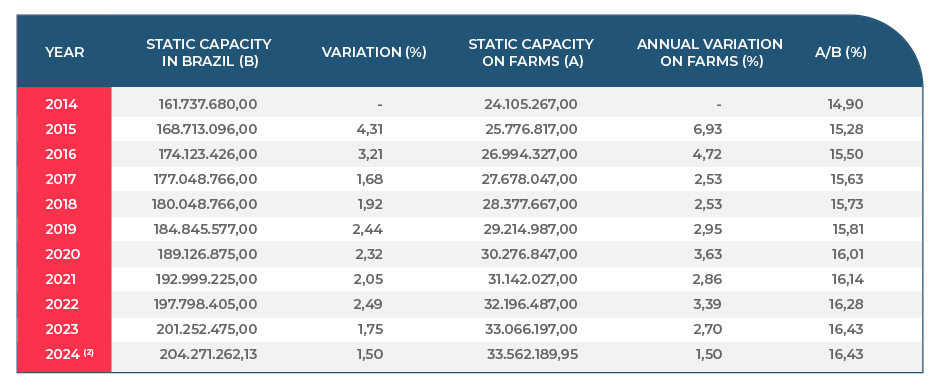

Brazil currently has a static storage capacity of 204.27 million tons (Conab), which is equivalent to 66.68% of the estimated production. Only 16.43% of this static capacity is located on farms (33.56 million tons). Refer to Table 2.

Tabela 2.

Static capacity on farms, in tons, and percentage of total capacity.

² Projection considering a 1.5% increase in static capacity from 2023 to 2024.

Source: Conab / Prepared by Scot Consultoria.

Advantages of self-storage for producers

Having storage space on the property can be highly beneficial for both farmers and ranchers. Sometimes, the lack of this space leads to missed business opportunities, greater exposure to volatility in the road transport market, and logistical challenges, especially during peak harvest periods. This is due to factors such as the mismatch between grain-producing and consuming regions, as well as the difference between harvest and demand periods.

For the farmer, having their own storage structure offers advantages such as:

- Autonomy in marketing management (choosing the ideal time to sell their production, based on future price analysis, avoiding the natural market pressures during harvest time);

- Lower transportation costs (by not having to act during harvest months, the producer can avoid the “rush” when most of the production is being moved, and transportation prices are more volatile);

- Better grain quality (preventing exposure to the open air and protecting it from climatic variations);

- Agility (eliminating the time lost waiting in line at storage, collection, or intermediary units);

- Better standardization (controlled environment in terms of humidity, damaged grains, and impurities).

For ranchers, especially fattening ones, storing grain can also be a smart strategy. Having the ability to store grain on the property gives producers the power to choose the most opportune times to purchase their supplies.

In this way, ranchers gain additional protection against market fluctuations, which can make a significant difference in their profitability.

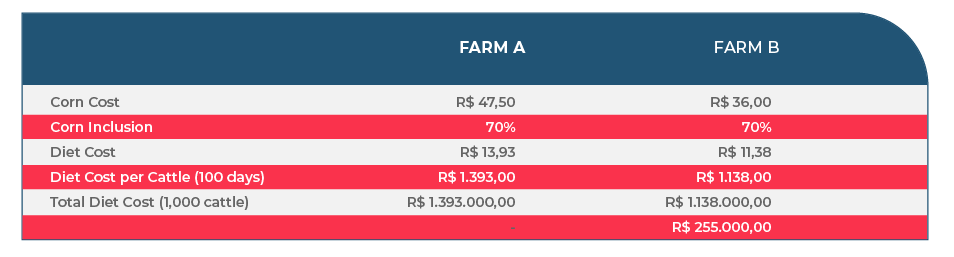

Let’s take as an example farm A, which has no grain storage facilities, and farm B, which has the necessary storage facilities. Both farms operate on a full cycle and finish off native steers in confinement.

Located in the city of Rondonópolis, MT, both farms will finish 1,000 steers in April.

Farm A, lacking storage facilities to begin fattening in April, bought corn in January 2024 to be delivered in February of the same year. The purchase price of the input was R$47.50 on 01/12/2024 (Scot Consultoria).

On the other hand, at Farm B, with storage capability, the producer made their strategy at the beginning of the harvest year (July-June 2023) and, taking advantage of the sharp decline in the 2022/2023 grain harvest, purchased their corn for R$36.00 on 12/07/2023 (Scot Consultoria).

Image 1 shows the variation in corn prices over the past year.

Image 1.

Corn price variation in the Rondonópolis – MT region.

Source: Scot Consultoria

To demonstrate the impact of the storage strategy on farm profitability, we will set up a scenario where all other variables are similar for both farms (diet, operating costs, feed efficiency, etc.), considering only the difference in corn acquisition cost. For this, a standard 70% corn inclusion in the fattening cattle diet was established.

For Farm B, we will set a daily diet cost of R$11.38 per head (average diet cost in the state of Mato Grosso according to Confina Brasil 2023 data), with corn purchased at R$36.00. Meanwhile, the diet cost at Farm A, considering only the difference in corn price, purchased at R$47.50, would be R$13.93 per head/day.

Based on a 100-day confinement period and a herd of 1,000 cattle, the savings that Farm B would have over Farm A would be R$255,000.00, solely linked to the ability to purchase the input at a better window. Refer to Table 3.

Table 3

Comparison between the scenario of Farm A (no storage structure) and the scenario of Farm B (with storage structure).

Source: Scot Consultoria

In a constantly evolving, increasingly competitive scenario with narrower margins, grain storage is a strategic element that can bring advantages and higher profitability to the activity.

As such, this tool can and should be considered by producers looking to eliminate bottlenecks and build a more intelligent management of their financial resources.