The goal of any feedlot is to ensure maximum efficiency in the shortest time possible, with the best profitability. For this reason, health management upon the arrival of livestock plays a fundamental role in ensuring their health and performance throughout their stay in the feedlot facilities, guaranteeing productivity and safety in the meat production chain.

Standardization and acclimatization

In the feedlot system, the cattle batch is handled upon arrival and remains in the facilities until slaughter. The origin of the cattle can vary, from those raised on the farm itself (native breeds) to those purchased from third parties. These can either be bought at weaning (which can be normalized during the rearing period) or older (steers/cull cattle), coming from various sources.

One of the first aspects to consider is the cattle’s journey to the feedlot. In addition to dehydration, stress causes the release of chemical mediators that can reduce immune response, and it is crucial to provide an appropriate reception environment to minimize this impact.

Mixing cattle from different places makes it difficult to standardize the herd’s health history and increases exposure to infectious agents, a predisposing factor for the development of diseases.

When the cattle arrive, there is an opportunity to homogenize the herds. Therefore, it is essential to adopt personalized protocols that consider the origin of the purchased cattle and the particularities of each batch.

Triad: clostridiosis, parasitosis, and respiratory diseases

The bovine respiratory disease complex (BRD) remains the biggest issue in terms of cattle health in feedlots. Parasitosis is also a concern, especially in herds with uncertain health histories. In addition to issues related to fractures, accidents, and nutrition, clostridiosis is one of the main diseases affecting confined herds.

According to a survey conducted by Confina Brasil in 2023, more than 80% of the feedlots surveyed carry out a basic entry protocol, which includes deworming, prevention of clostridiosis, and the administration of respiratory vaccines.

The first dose of vaccination against clostridiosis and the main respiratory diseases should be administered about 30 days before entry into the feedlot, followed by a booster dose on D0 (entry day). Additionally, protection against ectoparasites is recommended upon cattle arrival, as tick infestations can cause weight gain delays and production losses.

Preventing to avoid remedy?

In feedlots, any issue that interferes with the cattle’s good performance can have a significant impact on the farm’s profitability.

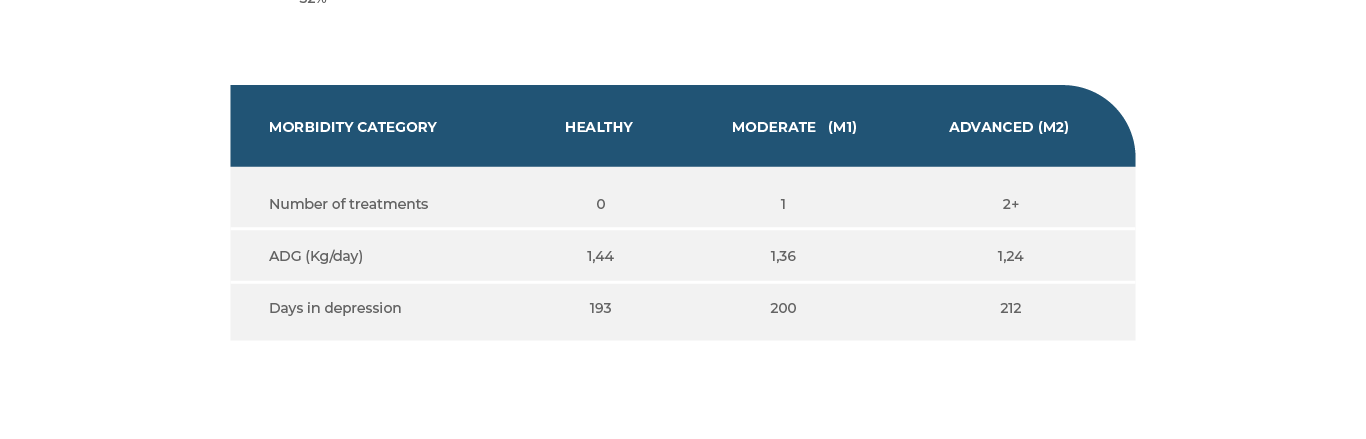

The economic repercussions of ineffective health management have been studied for decades. A study by Bateman et al. (1990) observed that cattle affected by pneumonia during confinement lost 14 kilos compared to cattle unaffected by the disease. Similarly, Smith (1996) monitored a feedlot for 28 days and identified a reduction of 23 kilos in the weight gain of sick cattle compared to healthy cattle. More recently (2007), Waggoner and his colleagues worked to assess the impact of morbidity in feedlots on average daily gain (ADG) and carcass characteristics. For better visualization, the results are shown in image 1.

Image 1 – Impact of morbidity in the feedlot on ADG and carcass characteristics.

Source: Waggoner, J.W et al., 2007 / Adapted by Scot Consultoria

Healthy cattle (S) achieved an ADG of 1.44 kg, while cattle with moderate morbidity (M1), which received up to one veterinary treatment, recorded an ADG of 1.36 kg. Cattle with advanced morbidity (M2), which required up to two treatments during confinement, had an ADG of 1.24 kg. The number of days cattle remained in the feedlot also increased, with the following results: 193 days for group S, 200 days for group M1, and 212 days for group M2.

Therefore, in addition to the decrease in productivity and the extended stay of sick cattle, morbidity rates are strongly associated with treatment costs and economic losses due to cattle mortality.

Sanitation rounds

The so-called “sanitation rounds” are inspections conducted in fattening pens to evaluate the batch and identify health problems at an early stage, allowing necessary actions to prevent or treat diseases during the cattle’s stay in the feedlot.

The two to three weeks following cattle introduction into the feedlot constitute the most difficult period. For this reason, animals must be monitored more frequently.

Cattle remain confined for an average of 90 to 100 days. The frequency of these inspections can vary during the feedlot rotation. These inspections are more rigorous during the first three weeks, with up to two rounds per day recommended during this phase. After this initial period, the frequency is reduced to one inspection per day, continuing for approximately six weeks, with a total of about 40 days.

After 40 days, alternating inspections (every other day) can be performed, but in case of disease outbreaks, it is crucial to resume daily inspections.

During the rounds, it is important that the sweeping is done evenly across the entire pen, always encouraging the movement of the cattle.

Conclusion

Given the significant impact of morbidity on cattle performance during confinement, it is essential to highlight that health costs represent less than 1% of the total costs of this process, as noted by Martins (2016). Therefore, neglecting vaccination or parasite control is unjustifiable, as these practices lead to significant production losses that directly compromise the system’s profitability.

Managing cattle entering the feedlot is crucial and requires an adapted approach, considering the specifics of each farm. By applying appropriate health protocols, it is possible to ensure not only the welfare but also the productive performance of the herd, avoiding losses during this stage and contributing to the profitability of the operation.